[UPDATE: We have a cover! And don’t forget to get your preorder in: You’ll get your copy hot off the presses on September 17, 2024.]

There’s no doubt something big happened. Historians know it. People at the time knew it. When it came to the startling changes sweeping their cities in the first decades of the 1800s, people in Philadelphia, Boston, Baltimore, and New York could hardly stop talking about it.

In some ways, historians have painstakingly mapped the changes, marked the ways that US cities developed modern municipal institutions such as prisons, hospitals, and almshouses. And historians of education have noted a similar change—one with similarly revolutionary results—in the birth of modern public-school systems. We know it happened. We know when it happened. And we know it was big. But so far, when it comes to schools, we don’t know how it happened.

Historians are well aware that it had something to do with the overhyped promises of one unsavory celebrity. At the time, the narcissistic London reformer Joseph Lancaster was one of the world’s most famous people, taking way more credit than he was due for his simplistic education “system.” In 1818, by special invitation, Lancaster emigrated to New York to bring his system to that city and all the cities of the US. America’s city leaders thought they were investing in the future. What they did not know was that Lancaster’s modern magic was a sham; he had built his supposed miracle on a foundation of embezzlement, fraud, and the sexual abuse of his closest students.

The key to understanding the complicated birth of modern urban public-school systems has been hidden by Lancaster’s wild claims. Urban elites in the US leaped to give Lancaster the credit he didn’t deserve. They desperately hoped he was right; they hoped he’d give them the modern public schools they were yearning for. Most important, they hoped his impossible promise could be true; namely, that he could solve all their problems without costing an extra dime.

At the time, Lancaster’s ideas were all the rage. He was feted and celebrated by kings and presidents around the world. Pennsylvania and Massachusetts passed laws mandating Lancaster’s London methods in their new city schools. Albany, Savannah, Cincinnati, Detroit, Baltimore, and a host of other cities followed. They invested in Lancaster’s fantasies; they believed their new schools would transform their cities and save them from uneducated mobs.

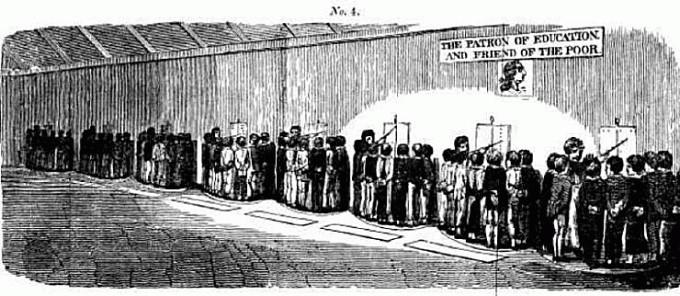

Lancaster’s system was fairly simple. He promised he could build cheap schools to corral the hordes of low-income children in America’s cities. Instead of expensive adult teachers, Lancasterian schools had children teach one another to read, write, and behave properly. Lancaster and his followers thought it would change everything. Lancaster told the world that his schools would “ utterly exterminat[e] ignorance” from the entire planet. Mayor De Witt Clinton of New York City called the system “a blessing sent down from Heaven to redeem the poor and distressed of this world from the power and dominion of ignorance.”

utterly exterminat[e] ignorance” from the entire planet. Mayor De Witt Clinton of New York City called the system “a blessing sent down from Heaven to redeem the poor and distressed of this world from the power and dominion of ignorance.”

America’s city leaders poured the equivalent of millions of dollars into the scheme. They built huge specialized schoolbuildings. They bought Lancaster’s teaching machines and offered him a huge salary. What they didn’t do was inquire too closely into what had happened in London. If they had, they might have saved themselves some heartache and expense, and they would have sent America’s cities down a very different path.

My new book tells the story: it’s the story of America’s original municipal sin, when white elites assumed their answers were the answers. Reformers were transfixed by Lancasterianism. It was modern, it was urban, it was high-tech…it was all the things they assumed their solutions would need to be. They thought it would save their cities from the dangers of modern urban life. They didn’t look elsewhere, closer to home, to notice that other kinds of public schools were succeeding and had been for a while. They didn’t listen to the voices of their lower-income neighbors, who knew what they wanted public schools to look like, and knew it wasn’t what Lancaster described. If the Lancasterian reformers had only listened, they might have discovered the achingly obvious key to the creation of modern public-school systems: public schools need adequate resources and they need to respond to community needs. When Lancaster’s simplistic ideas failed—as it seems painfully clear in retrospect they must—it was left to non-famous, non-elite teachers, students, and parents to create urban public-school systems from the wreckage left behind. And that’s what they did.

PREVIEWS–Lancaster may have died a grisly death way back in 1838, but the legacy of his failed reform is depressingly relevant to today’s schools:

- At the Atlantic, I gave the real history of religion in public schools, a history that blows big holes in recent Supreme Court decisions.

- At the Washington Post, I examine the way Chief Justice Roberts mis-read the history of religion in early public schools.

- When schools run into problems, reformers have always blamed teachers. It’s a story two hundred years old–I lay it out in the Washington Post.

- With Victoria Cain for Kappan, I tackle the eternal question of school tech. What did the Lancasterians do? Why did it fail? What’s the lesson for today’s school leaders?

- The pandemic raised centuries-old dilemmas of student attendance. For the Washington Post, I dig up the history. Turns out students have always held veto power over public schools.

REVIEWS: What have people said about the book?

- Dr. Ben Justice, author of books such as The War That Wasn’t: “This colorful, easy-to-swallow account of America’s original ed reform huckster is stern medicine for wannabe saviors and would-be rubes. With deep expertise and keen wit, Professor Laats has given us a Joseph Lancaster for the ages.”

- Dr. Johann Neem, author of books such as Democracy’s Schools: “Since Joseph Lancaster’s time, politicians have fallen for education reformers who hawk easy fixes for complex problems. As Adam Laats makes clear in this wonderful book, Lancaster may have been America’s first charlatan reformer, but he was certainly not the last. For our children’s sake, let’s hope we heed the lesson.”

- Dr. William Reese, who knows more about early US public schools than anyone, called it a “captivating, landmark study.”

- Dr. Mark Boonshoft, who wrote the prize-winning book on academies and the rise of public schooling in the US, said it was an “astonishingly original and compelling origins story.”

- Dr. Nancy Beadie generously said the book had “both a compelling narrative and an insightful analysis.”

13 thoughts on “Mr. Lancaster’s System: The Failed Reform that Created America’s Public Schools”