Quick options {Click on a book or scroll down to read about em all}

Work in Progress:

Published:

- Creationism USA: Bridging the Impasse on Teaching Evolution (Oxford University Press, 2020)

- Fundamentalist U: Keeping the Faith in American Higher Education (Oxford University Press, 2018)

- Teaching Evolution in a Creation Nation, with co-author Harvey Siegel (University of Chicago Press, 2016)

- The Other School Reformers: Conservative Activism in American Education (Harvard University Press, 2015)

- Fundamentalism and Education in the Scopes Era: God, Darwin, and the Roots of America’s Culture Wars (Palgrave Macmillan, 2010)

What’s Cookin’:

School Children: The Real Founders of American Public Education

[Update: Here we go…starting the outlining, and very grateful to the many sources of funding and research material. Special thanks to the National Endowment for the Humanities, which sponsored a year of full-time work on the book. Thanks also to the American Antiquarian Society, Massachusetts Historical Society, and New York State Archives, and also to the Charleston County (SC) Public Library, Georgia Historical Society, Newberry Library, Clements Library at the University of Michigan, North Carolina State Archives, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Louisiana State University Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections, Syracuse University Special Collections, and Swarthmore College Special Collections.]

Why is school reform so difficult?

There are good answers out there: I still remember the first time I read David Tyack’s and Larry Cuban’s answer. It blew my mind. Once they explained it, the truth seemed so obvious. It lined up so well with what I had seen as a high-school teacher. Over and over, reformers with too much power and too little experience in real schools had ignored the simple, essential fact: Teachers embrace reforms that help them do the difficult things they are already trying to do. They ignore the ones that don’t.

In my new book, I’m trying to spell out the other obvious answer from history, an answer so obvious I don’t know why it isn’t talked about more often. The most important people in schools—and the ones with the most impact on how schools look and function—have been strangely ignored by historians and policy-makers alike, even though their choices have been inarguably the most influential in shaping public schools.

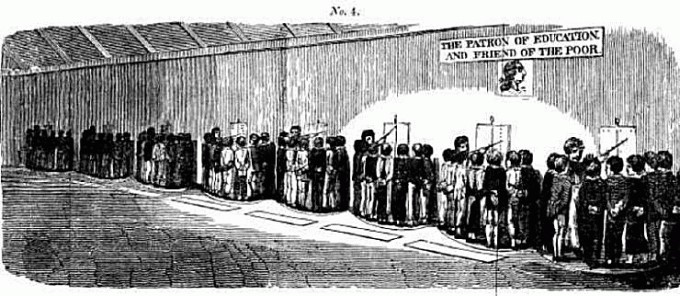

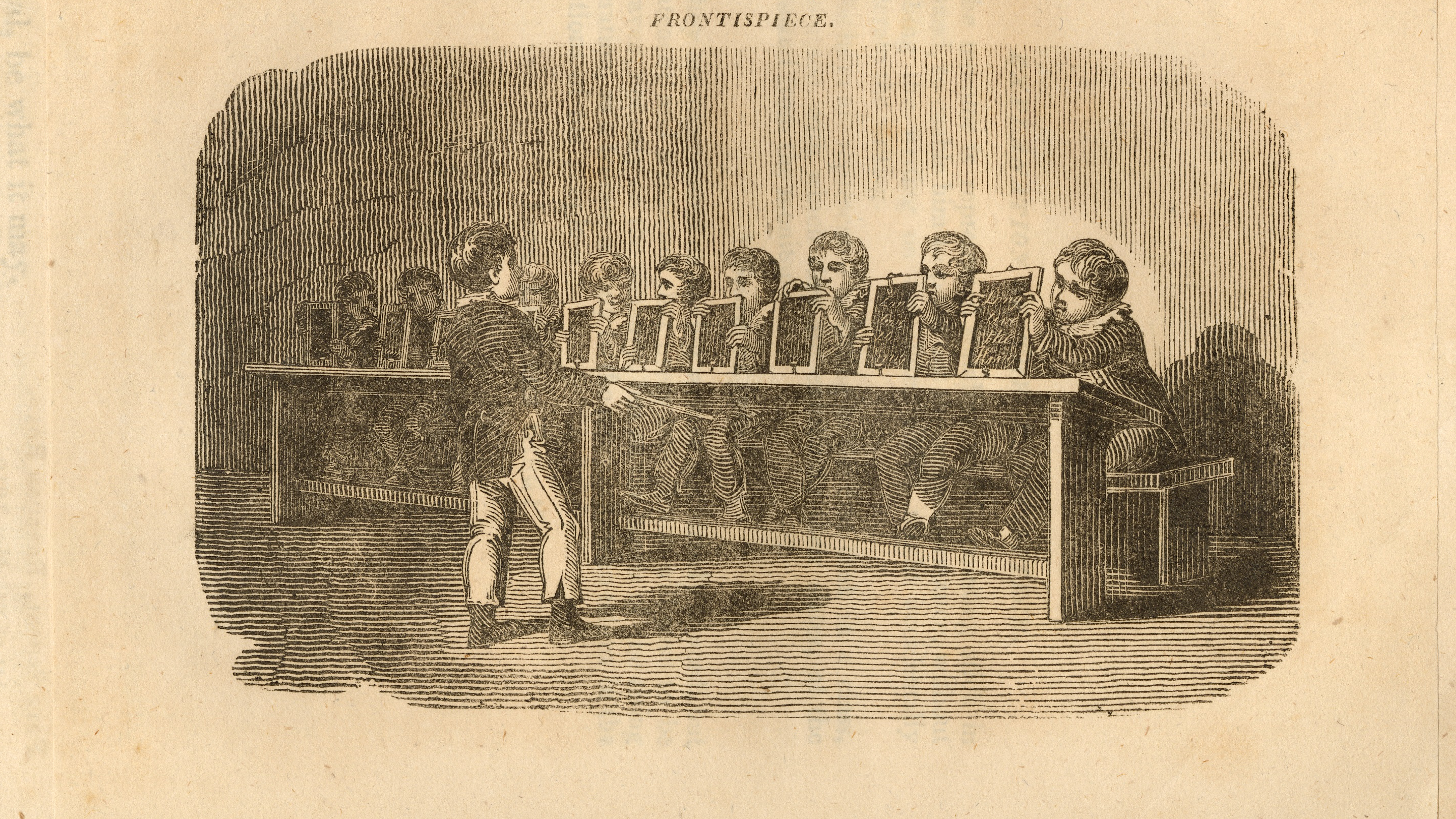

I’m talking, of course, about the school children themselves. In my new book, I’m arguing that children decisively shaped US public schools as schools evolved from 1790 to 1860. It was children who determined the failure or success of every structure, every plan, and every reform idea. Certainly, adults were important. But when we wonder why public schools don’t look the way Joseph Lancaster or Horace Mann envisioned them, we need to examine the most important answer—the influence of children.

Children didn’t just tweak schools here and there. No, in every fundamental aspect—who was considered a possible teacher, what textbooks could be used, how often schools would meet, whether teachers could beat children, whether Black and white children would attend together, what religion would be preached—in every aspect, the role of children was the most important factor.

Putting children at the center of the story does more than just offer a better explanation for the tortuous history of school-reform efforts. It also allows the story to expand beyond the limits of adult-centered histories. Without considering the children—all the children—histories end up focusing on white, middle-class-dominated institutions. This has been true for even the best, most nuanced histories, like the late Carl Kaestle’s Pillars of the Republic (1983). Great historians have tried to expand the story, but focusing on adults means replicating adult divisions. It means telling the history of US public schools as a white-dominated enterprise with some important exceptions.

On the other hand, for the past fifty years historians have been digging into the lives of children in the past. Scholars like Kabria Baumgartner, Karen Sànchez-Eppler, Holly Brewer, Patricia Crain, Courtney Weikle-Mills, and many more have studied what children were doing, what they were thinking, and what adults were thinking about them.

But no one has connected that scholarship to the early evolution of public schools. I will put children at the center of that story, where they belong. When you do that, you can’t help but acknowledge the painfully obvious fact of antebellum American life. Namely, most children spent most of their time doing things other than attending school. Schools did not shape children–children shaped schools. Children’s lives were the things that nurtured and guided schools as one possibility, or, for many children, one impossibility.

******************************************************

Mr. Lancaster’s System: A Failed Reform and the Birth of American Public Schools, 1800-1840

PREVIEWS–Lancaster may have died a grisly death way back in 1838, but the legacy of his failed reform is depressingly relevant to today’s schools:

- Why should we care about Lancaster? Check out this interview with Historians and their Histories, the podcast from the Massachusetts Historical Society. (August 2025)

- Thanks to Max Jacobs and the New Books Network for hosting this interview about the book. (February 2025)

- Give a listen to our conversation at the great edu-podcast Have You Heard—where we talk about the long tradition of educational hucksterism. (October, 2024)

- Why did SCOTUS approve of a praying coach? According to Neil Gorsuch, it was because that was what the “Founding Fathers” would have wanted. From Florida, we hear that the “Founding Fathers” would have wanted more chaplains in public schools–just not Satanic ones. Other conservatives, too, in Louisiana and Oklahoma, base their trashing of norms on what they think the “Founding Fathers” would have wanted in public schools. Over at Current, I offered a look at what the real founding fathers of public schools really wanted. Spoiler: it wasn’t more Jesus. (September, 2024)

- Oh, Ronny. I know you’ve had a tough year, but you can’t just make stuff up. When Gov. DeSantis signed a new law allowing religious chaplains in public schools, he said he was just doing what the “founding fathers” wanted. But the real history says different. As I argued at The New Republic, “DeSantis is doing his best to bring the Founders’ nightmares to life.” (April, 2024).

- Careful what you wish for, Justice Gorsuch. He thought he scored a huge conservative victory in 2022 by cramming Jesus back into public schools, but the way he did it will actually push Jesus out. The history is obvious, but conservatives just don’t seem to know it. Here it is at the Washington Post. (December 2022)

- At the Atlantic, I gave the real history of religion in public schools, a history that blows big holes in recent Supreme Court decisions.

- At the Washington Post, I examine the way Chief Justice Roberts mis-read the history of religion in early public schools.

- When schools run into problems, reformers have always blamed teachers. It’s a story two hundred years old–I lay it out in the Washington Post.

- With Victoria Cain for Kappan, I tackle the eternal question of school tech. What did the Lancasterians do? Why did it fail? What’s the lesson for today’s school leaders?

- The pandemic raised centuries-old dilemmas of student attendance. For the Washington Post, I dig up the history. Turns out students have always held veto power over public schools.

REVIEWS: What have people said about the book?

- Dr. Ben Justice, author of books such as The War That Wasn’t: “This colorful, easy-to-swallow account of America’s original ed reform huckster is stern medicine for wannabe saviors and would-be rubes. With deep expertise and keen wit, Professor Laats has given us a Joseph Lancaster for the ages.”

- Dr. Johann Neem, author of books such as Democracy’s Schools: “Since Joseph Lancaster’s time, politicians have fallen for education reformers who hawk easy fixes for complex problems. As Adam Laats makes clear in this wonderful book, Lancaster may have been America’s first charlatan reformer, but he was certainly not the last. For our children’s sake, let’s hope we heed the lesson.”

- Dr. William Reese, who knows more about early US public schools than anyone, called it a “captivating, landmark study.”

- Dr. Mark Boonshoft, who wrote the prize-winning book on academies and the rise of public schooling in the US, said it was an “astonishingly original and compelling origins story.”

- Dr. Nancy Beadie generously said the book had “both a compelling narrative and an insightful analysis.”

- One of my fave education writers and thinkers, Peter Greene, had this to say: “Laats combines thorough scholarship with bright and accessible writing. Mr. Lancaster’s System is a fascinating tale that at once illuminates a little-noted chapter of history while also shedding light on our present. For anyone with even a passing interest in education policy and history, this is a must-read.”

- For The Baffler, Jennifer Berkshire connected the dots. Today’s billionaires keep repeating the mistakes of the Lancaster generation. As Berkshire puts it: “A recent profile of [billionaire Jeff] Yass put it this way: ‘Convinced that a free-market school system is the solution to Philly’s—and the country’s—big problems, the incredibly wealthy, notoriously secretive suburban businessman is bankrolling an initiative to change the way we teach children here and across the nation. Could he be right?’ Laats’ history provides a definitive answer to this question: no.”

- At Religion & Education, Kathleen Sellers offers a great review:

- “More than simply providing evidence of this thesis, which Laats does compellingly, this book illustrates how modern problems in US education are not, in fact, new. For at least two centuries, public schools have only been effective when they are adequately funded by taxes and respond to the needs of diverse stakeholders. Indeed, perhaps the greatest strength of this book is that Laats pays close attention to the diversity of voices who were impacted by and contributed to historic educational reforms.”

- Marcelo Caruso–the leading authority on Lancasterian reform world-wide–offered some great insights at H-Soz-Kult:

- “Laats’ book is a major reinterpretation of both the urban experiments in focus and the ensuing developments known as the Common School Movement. He delivers a rigorous, but also vivid analysis of the Lancasterian movement in the main urban centres of the United States. The book overcomes the local focus of the considerable historiography dealing with the evolution of urban public systems in these decades. It also diverts our attention to the enduring racist issues at stake in some of these schools of purportedly charitable character, supported by groups related to the opposition to slavery. Moreover, Laats tapped into the mostly unused treasure of Lancaster’s papers, held at the “American Antiquarian Society” in Massachusetts, combining his narrative of enthusiasm and deception with an individual story of acute narcissism, plain lies and a desperate search for money and prestige.”

- Dr. Shanna Peeples offered a substantive, thoughtful review at Urban Education:

- “Laats’ greatest contribution lies in excavating this link between early notions of educational improvement and present-day echoes in perennial technological miracles that promise comprehensive learning on the cheap. By documenting America’s earliest systematic experiment in scaling educational services for communities historically described as “the urban poor,” he provides essential context for understanding recurring patterns. The book balances historical detail with accessible prose, skillfully using primary sources to reconstruct the experiences of students, parents, and teachers rather than relying solely on elite perspectives.”

*****************************************************************

Creationism USA: Bridging the Impasse on Teaching Evolution

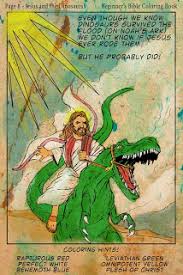

Who are America’s creationists? What do they want? Why do they think Jesus rode around on a dinosaur? In my new book, I argue that common misconceptions about creationism have led us into a full century of hapless and unnecessary culture-war histrionics about evolution education and creationism. In fact, tough as it might be to notice, America does not now and never has had deep, fundamental disagreement about evolution.

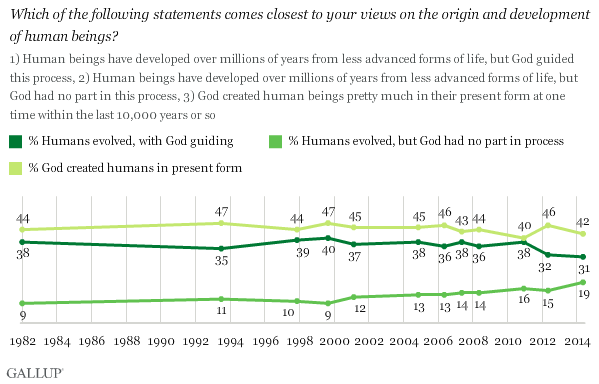

If we only read the headlines, that statement might seem obviously false. After all, as we’ve seen in Gallup polls since the 1980s, nearly half of Americans say they think our species was created pretty much as-is within the past 10,000 years. And of those creationists, about a quarter have been to college.

For those of us who aren’t creationists, it is difficult to understand how so many people—apparently even educated people—can cling to such outlandish anti-scientific ideas. Yet it doesn’t take much time to find more evidence everywhere we look.

In recent state school-board elections in Texas, for example, front-runner Mary Lou Bruner thought dinosaurs had survived Noah’s flood on the ark. For what it’s worth, Bruner was also convinced that President Obama had put himself through law school by working as a prostitute. It’s not only down in Texas. When President Trump picked his cabinet, he chose ardent young-earth creationist Ben Carson to head the Department of Housing and Urban Development. Education Department Secretary Betsy Devos has done more than just endorse creationism; she has funded creationist pundits and schools.

Are they simply dummies? Wacky conspiracy-theorists like Mary Lou Bruner sure seem like it. But that label is hard to accept in the case of Dr. Carson, a leading pediatric neurosurgeon. Can someone be a dummy if he invents a new way to operate on baby’s brains? Explaining away creationism as mere stupidity doesn’t seem to fit. Yet it is easy enough to find people who will tell you that it does. Atheists such as Oxford’s Richard Dawkins famously dismissed creationism as merely an outbreak of ignorance, insanity, or sheer wickedness. For some people, Dawkins’ explanation might be enough.

For the rest of us, however, Dawkins’ angry harangues don’t really help. We might not like creationism or understand creationists, but the answers don’t seem as stark and simple as Dawkins says they are. So where can we go next? If we hope to understand America’s culture wars over creationism, we tend to get caught in an unproductive loop. The most active pundits and writers about creationism tend to be the angriest on both sides. Radical creationists tell us that evolution equals atheism. Radical atheists agree, and insist that creationism is only for the radically ignorant.

Not surprisingly, the truth is more complicated. Though it might not seem possible to the casual observer, the battle lines in American culture between creationism and evolution are not really between creationists and the rest of us. There is not a stark and simple divide between religious creationists who think the earth was made 6,000 years ago and atheist scientists who disagree.

Americans do have significant disagreements about creationism, though, and once we press into the history of the creationism culture wars, those actual battle lines leap into high relief. Hard as it may be to believe, the real battle is not between creationists and evolution. Americans are not and never have been locked in a culture war between creationists and evolution. We could not possibly be, for two fundamental reasons. First, today as in the past, almost all Americans are creationists of one type or another. At the same time, almost all Americans, including creationist Americans, want their children to learn rigorous, mainstream evolutionary science.

These facts aren’t hidden, yet they remain shocking to those who do not understand the real world of American creationism. Creationism USA explains the history and current state of America’s true battles over creationism. It offers a nuanced but simple prescription to solve them.

The book’s recipe is straightforward. In order to understand the creationist culture wars—the real ones, not the phony headlines—we need to begin with a better understanding of creationism itself. Next, we need to clarify the areas on which we really do disagree about evolution. They are not insignificant, but they can be overcome.

All of us—religious, secular, and not sure—need to recognize a few things: 1.) what creationism truly is in twenty-first century America and 2.) what we really want out of our public schools. In addition, all of us need to accept the fact that we can’t force other people to admit we’re right. In short, we might not agree about religion and science…but that’s okay. The division we’ve gotten used to fighting about isn’t really about those things at all.

In this book, I’m arguing that our true division about creationism is not between creationists and evolution-lovers, but between two other types of believers. Once we recognize this fundamental truth about American creationism we can notice new ways to get over our century-old go-nowhere battles about textbooks and Darwin.

Will everyone agree? Certainly not. But the fiercest opposition to this program will be from the very radicals who have warped and distorted our conversations about creationism for a full century. Once we understand real American creationism, we will be able to see how insignificant those radical voices really are.

Cheapskate Corner! Want to check out the book, but don’t want to cough up twenty bucks for it?

- At Forbes, Peter Greene offered an insightful review:

- “Laats provides an thoughtful and insightful guide to one of our most persistent education debates, and in doing so, may also provide some insights into the cultural war issues facing schools today.”

- Thanks to the folks at Nature for asking about the history. With universities under attack in the 2020s, I offered a look at the lessons from the anti-evolution battles of the 1920s.

- How did the creationism of the 1920s set the pattern for enduring movements to ban and burn books from America’s schools? I laid out the history for The Atlantic.

- How about this excerpt featured at Friendly Atheist?

- Or this piece at Anxious Bench?

- Maybe this argument I made about Trumpism and radical creationism at History News Network?

- Short on time? You can read this interview with my campus research newsletter.

- …or listen to this longer interview with Chris Voss on the Chris Voss Show podcast.

- You could give a listen to the Holy Post Podcast with Phil Vischer (yes, the “Veggie Tales” guy). He asks: Where did Young Earth Creationism come from? How new is it?

- At Kappan, I take on the myth of the “eternal monkey trial.” It might seem like America keeps fighting the same fight about creationism, but in fact evolution education has made huge strides.

- Why the book? Check out the interview at Righting America. What is a “radical” creationist? What does creationism have to do with Trumpism?

The reviews are coming in:

- At Science Education, John Rudolph of the University of Wisconsin–Madison offered a smart, insightful review. There’s a paywall, but Prof. Rudolph asks some tough questions and gives some positive answers. For example: Is there any need for yet another book about creationism? Dr. Rudolph: “After spending some time with this highly readable and engaging book, I am happy to report that [Creationism USA] offers something quite new indeed.” Or this one: Why have creationist culture wars lasted so long? Dr. Rudolph: “In a nutshell, [Creationism USA] complicates the longstanding us‐versus‐them, creation–evolution narrative, and demonstrates convincingly that a more accurate framing is really us versus us.”

- In Reports of the National Center for Science Education, Anj Petto nailed it. What’s the book about? As Petto writes, “we need to make it clear to the non-radical contingent of creationists that evolution education does not threaten their values. But the starting point of this process is to listen to what creationists really are saying about their concerns about the place of evolution in public life. If you are interested in promoting the acceptance of evolution among the general public, you should read this book!”

*************************************************

Fundamentalist U: Keeping the Faith in American Higher Education

Oxford University Press, 2018

If you want to run for President as a Republican these days, there seems to be a new requirement. In addition to shaking hands, kissing babies, and eating barbecue, every GOP hopeful since Reagan has added a stop at a conservative evangelical college. Why? What do these schools mean in the fractious politics of culture-war America?

In my new book, Fundamentalist U: Keeping the Faith in American Higher Education, I’m exploring the complex history of evangelical and fundamentalist higher education. In many ways, these schools have functioned as institutional hubs in the kaleidoscopic world of conservative evangelicalism. From Reagan to Romney, from Cruz to (Jeb) Bush, politicians hoping to woo the conservative religious vote have visited conservative schools such as Bob Jones and Liberty University.

When the GOP contest kicked off for 2016, the tradition continued. Texas Senator Ted Cruz jump-started the race in March, 2015. Guess where he headed to make the announcement? And when it came time for Liberty’s 2015 commencement address, was it any surprise that Liberty welcomed Governor Jeb Bush as a speaker? And today, the connections between the Trump White House and the Falwell mega-campus are tighter than ever. When it came time for President Trump’s first commencement address, there was little doubt where he’d go.

It makes sense. Schools such as Bob Jones and Liberty, as well as Wheaton College, Biola, The King’s College, and a host of other institutions, have educated generations of evangelicals in the distinctive intellectual and cultural traditions of their faith. Students at these schools agree to more rigid lifestyle rules than they would on secular campuses. And they agree to have their educations shepherded by faculties who have signed on to detailed statements of faith. Just as alumni of the Ivy League might brag about their alma maters, so alumni of these schools feel a distinct connection to their colleges. Politicians hoping to prove their conservative credentials want to jump on that bandwagon.

But that does not mean that these colleges are somehow monolithic. The differences between these schools often loom larger than their similarities, at least in the world of evangelical Protestantism. What does it mean to be “creationist?” What changes are healthy, and what are dangerously heterodox? And what is the proper, Godly relationship between men and women? There is no single “evangelical” answer to these questions. Just as at pluralist campuses, evangelical campuses have been rocked by controversy on all these issues.

But there is a palpable sense of connection. There is something that unites the fractious world of evangelical higher education. And in this book, I’m asking questions about it: What did such schools hope to teach each new generation of evangelical student? How did they hope to raise up new generations of faithful young people in a country that was slipping farther and farther into secularism? And, importantly, how did students respond to these efforts?

If we hope to understand America’s continuing culture wars, we must make sense of the many meanings of these institutions. After all, our culture wars aren’t between one group of educated people and another group that has not been educated. Rather, the fight is usually between two groups who have been educated in very different ways.

Cheapskate Corner: Want to read more, but nervous about coughing up twenty bucks for the book? You can read author interviews around the interwebs:

- Why is it so difficult to lead an evangelical college? Read my interview with the Trollingers at Righting America.

- Why Fundamentalist U? Read an author interview at Inside Higher Ed.

- Read more at Chronicle of Higher Education.

- Listen to an author interview at Phoenix’s KJZZ.

- Keeping the faith–read an author interview at Religion & Politics.

- Race, confessional theology, and Marilynne Robinson: A talk about Fundamentalist U (and other things) with Adam Holland of The Daily Brew.

- Can we ever get beyond our culture-war prejudices? Can studying schools help us understand religion? A talk about Fundamentalist U with Professor Andrea Turpin at Religion in American History.

- What do evangelical colleges mean to those of us who aren’t (at all) evangelical? Listen to my interview with Friendly Atheist Hemant Mehta to find out.

- What are three reasons to read Fundamentalist U? Check out Justin Taylor’s recommendation at The Gospel Coalition.

The reviews are coming in:

- Professor John Compton pairs Fundamentalist U with R. Marie Griffith’s Moral Combat in the LA Review of Books. Compton’s verdict? Fundamentalist U “offers an invaluable introduction to the esoteric world of Christian higher education. Few existing studies offer this level of insight into the inner workings of schools like BJU and Liberty.”

- In the Wall Street Journal, Naomi Schaefer Riley had some nice things to say and some insightful reflections. For example, why do so many evangelical colleges love President Trump so much? As Riley puts it, “Caught between the vast changes in American higher education and the religious families they are supposed to serve, fundamentalist colleges have had to be especially attuned to which way the cultural winds are blowing. Which may occasionally get them some incongruous commencement speakers.” Riley’s overall take? “Mr. Laats . . . takes a topic that could easily be treated with condescension and turns it into the occasion for a fascinating and careful history. His discussion of the racial policies of these schools is especially enlightening.”

- Professor Barry Hankins in Christianity Today: As Professor Hankins notes, the “family feud” between fundamentalists and evangelicals often took place on the campuses of evangelical colleges and universities. And, as Prof. Hankins puts it memorably, “With fundamentalism subject to such a fluid range of definitions, controversies often centered on the question of authority. In other words, who gets to define fundamentalism for the college? Is it the board, the president, the faculty, or the students (certainly not, unless you ask them)? This was not shared governance but something akin to WrestleMania.” . . . “Overall, Fundamentalist U is an exhaustively researched and well-written book, even when it dwells on episodes we might prefer to forget.”

- In Reading Religion, Andrew Gardner writes, “At its best, scholarship on religion and American higher education produces fascinating studies about the ways in which religion engages in a unique and complex network of educational institutions that, in many ways, is unparalleled in any other country. Adam Laats’s book, Fundamentalist U: Keeping Faith in American Higher Education, falls within [this] category.”

- In History of Education Quarterly, historian Andrea Turpin of Baylor University, the author of a fantastic, award-winning recent history of American higher education, had this to say: “As a sympathetic outsider to the institutions he studies, Laats pairs depth of research and analysis with a commitment to rigorous fairness to his subjects. In Fundamentalist U, Laats does not merely explain the internal logic of an interesting, but isolated, group of colleges and universities; he also raises critical questions about the nature of broader American higher education and culture in the twentieth century. . . . Laats is an engaging writer, and the book’s chapters are filled with fascinating stories cleverly told. . . . Fundamentalist U reshapes our mental landscape of twentieth-century American higher educational institutions and is essential reading for understanding both their history and their present.

- Yes! Thanks to leading historian of evangelicalism Matthew Avery Sutton for a great review in American Historical Review. As Professor Sutton writes, Fundamentalist U is “an engaging, well-researched study of an important, understudied, and underappreciated aspect of American culture and life. The schools that he analyzes have produced generation after generation of students who have had a major impact on American society and politics. . . . Fundamentalist U is an excellent book.“

- Another good one. From Harvard’s Andrew Jewett in the Journal of American History: “Fundamentalist U is a superb book and a significant contribution to the histories of U.S. religion and politics as well as higher education.”

- A meaty, insightful review by Tim Gloege, author of Guaranteed Pure, in Church History: “essential reading for anyone interested in the history of modern evangelicalism. . . .Fundamentalist U further challenges three persistent myths that have also been targets of the new evangelical historiography. First, it demonstrates evangelical “orthodoxy” was an aspiration, a dream—and a fleeting one at that. . . . Second, Fundamentalist U. challenges the myth of fundamentalist “withdrawal from culture” between 1920 and 1970. . . .Finally, Laats demonstrates the utility of defining evangelicalism as a social network anchored by educational institutions. . . . Fundamentalist higher education may be an oxymoron to many outsiders, but Laats has convincingly demonstrated it has been central to American evangelicalism.”

*******************************************

The Other School Reformers: Conservative Activism in American Education

Harvard University Press, 2015

[UPDATE: More good news! I just heard that this book has been awarded the History of Education Society’s Outstanding Book Award for 2015. Wow! I’m very grateful to HES and to the selection committee.]

What have conservatives wanted out of America’s schools?

What has it  meant to be “conservative” about American education?

meant to be “conservative” about American education?

When I started asking those questions a few years back, I went at finding the answers the wrong way. At first, I visited the archives of prominent conservatives such as William Bennett and the Daughters of the American Revolution.

But I realized that I was putting the cart before the horse. If I wanted to find out what made someone “conservative” about education, I couldn’t pick out the proper conservatives ahead of time. So, instead, I examined the four most famous educational controversies of the twentieth century. I looked to see who showed up to advocate the conservative position. Using this method, I identified what I call “educational conservatism.”

In short, the tradition of educational conservatism has ranged beyond any single self-conscious movement or organization. From the 1920s through the 1970s—and, I think, well beyond—conservatives have agreed on a few basic principles. First, conservative activists have rarely questioned their shared assumption that schools matter, a lot. Among conservatives just as among twentieth-century progressives, activists have assumed that what goes on in schools will determine what goes on in society. As a result, conservatives have insisted that schools must push a steady diet of religion and patriotism on their students. The specific meanings of proper public religion and patriotism have changed significantly, but conservatives have always insisted that schools must never wobble in their firm adherence to the inculcation of traditional values, however those values are understood at the time.

That’s my argument, anyway. Is it any good?

To find out, you can listen to an interview at National Review with John Miller.

Or read some reviews:

- In the pages of the Journal of American History, Kevin Kruse of Princeton University, author of One Nation Under God, had this to say:

Well researched, well written, and well argued, The Other School Reformers offers a clear, evenhanded account of conservative activism in public education.

- Or how about Andrew Petto’s take in the Reports of the National Center for Science Education, in which he says:

Laats’s analysis of the social and political contexts in which this [conservative] resistance [to educational reform] occurs makes this book a must-read for anyone interested in or hoping to effect educational reform—whether in the sciences or in other disciplines.

- No one knows more about conservative teachers and the history of efforts to teach anti-racism than Professor Zoe Burkholder. In the pages of the History of Education Quarterly, here are her thoughts on the book:

The Other School Reformers: Conservative Activism in American Education is the first comprehensive historical study of conservative educational activism in the United States. . . . Laats makes a compelling argument that a powerful tradition of educational conservatism has played a decisive role in shaping American public schools and culture from the 1920s through the present. . . . The Other School Reformers makes a vital contribution to the history of education by identifying a clearly discernable and politically powerful tradition of conservative educational reform in the United States since the 1920s. One of this book’s strengths is its ability to explain the connections between these four episodes separated by time and space, and also to account for such differences as the changing ways that conservative educational activists dealt with race and religion.

- Another good one from historian Emily Straus, in American Historical Review (January 2017) 122 (1): 189-190 (subscription required):

The Other School Reformers directly engages several historiographical discussions and will be of interest to historians in a variety of fields beyond the history of education and the history of conservatism. By looking at conservatives’ fights around education, the book fills in the shadow figures against whom progressives—a group that historians have written much more about—fought. It also broadens our understanding of conservatism in the twentieth century by illuminating the centrality of education. Any scholar interested in how to tell a national story through a local lens will also benefit from reading Laats’s work. By excavating conservatives’ activism around public school education and by helping to reframe the discourse around education, Laats’s account will enrich both historical and contemporary debates on education and politics.

- Then there’s Mike Wakeford’s opinion in the blog of the Society for US Intellectual History:

The Other School Reformers is about big ideas and big questions. At bottom it is a valuable portrait of how Americans vie, in an ongoing way, to answer the questions that matter most: Why do we educate? What are schools for? And, in the context of crosscutting claims about the intrinsic relationship between ‘education’ and ‘democracy,’ what has, does, and should each of those terms mean?

- And don’t forget Kunal Parker’s review essay in the Tulsa Law Review, in which he considers OSR along with Kevin Kruse’s One Nation Under God:

If we are wont to think that American conservatives mobilized in opposition to Communism or Socialism, secularism, or the political demands of women and minorities, both Kruse and Laats, but especially the latter, show us how much conservative opposition in America has been directed against a modernist philosophical tradition that is uniquely the country’s own. If American conservatives have long demonized unsavory ideas as foreign imports, they have also demonized the country’s own anti-foundational traditions.

******************************************

Teaching Evolution in a Creation Nation

University of Chicago Press, 2016

What do we want out of America’s schoolchildren? . . . out of America’s creationists? In Teaching Evolution in a Creation Nation, my co-author Harvey Siegel and I tackle these difficult questions head-on.

Harvey and I review the historical and philosophical involved in America’s long culture-war battle over evolution and creationism. Historically, I argue, creationism (in most of its religiously inspired variants) has worked like other forms of religious and cultural dissent. Philosophically, Harvey reviews the tricky definition of science, as well as the most common objections to evolution education.

In essence, we argue that the best way to understand creationism is as a form of educational dissent. By defining creationism that way, we can see some directions in which classroom policy should go.

Most important, we argue that the proper aims of public-school evolution education should be to inculcate a knowledge and understanding of evolution. No creationist-friendly variants should be allowed in science classes as science. But dissenting students must be allowed and even encouraged to maintain their dissent. We can’t insist that students believe this or that about evolution. Not in public schools, anyway. We must insist, however, that students know and understand that evolution is the best scientific explanation of the ways life came to be on this planet.

Among the tricky questions raised by our book are these:

1.) Is “belief” an inherent part of good evolution education? That is, should children in public schools be encouraged not only to know and understand certain facts about evolution, but to believe that evolution is really the best way to understand the roots of our species’ existence?

2.) Does it water down evolution education to allow dissenters to maintain their dissent, even in the face of overwhelming scientific evidence?

3.) From creationists’ perspectives, is it too much to agree that mainstream evolution science really is the best science? Will creationists agree that their ideas are more religiously inspired belief than legitimate scientific dissent?

4.) Can teachers in the real world walk this line between teaching facts about evolution and teaching belief in evolution?

What do people think? Early experts have given us some nice blurbs:

Glenn Branch, deputy director, National Center for Science Education

[Siegel and Laats] take two uncompromising positions: We must not compromise on evolution education and we must not compromise the rights of creationist students. Recognizing the fundamental principles at stake, their goal is to show how we can fully respect both considerations. The key is to distinguish understanding from belief. . . . [TECN] provides a scholarly treatment of a complex issue. The book is short and readable, however, reaching conclusions that can, and should, be implemented in all biology courses. And it may reassure creationists that their children will be treated fairly.

The reviews keep rollin’ in! Here’s what Professor Amy Lark of Michigan Technological University had to say in the pages of the American Biology Teacher:

Laats and Siegel manage to make this oft-discussed topic feel new and interesting….

The last few chapters are what set this book apart from most on the subject. Laats and Siegel firmly situate the evolution/creationism debate in the realm of culture, rather than science. Many evolution opponents worry that learning about evolution in school will challenge or insult their children’s faiths. The authors point out that this is not necessarily true. . . .Indeed, they argue, it is not the responsibility of science educators to make sure that students believe that evolution is true, but only to ensure that they understand how the process works. Belief, if it comes at all, will follow on its own. The authors acknowledge the new minority position of evolution opponents and explain that while they value multiculturalism and the protection of cultural minorities, “that doesn’t mean that their culturally specific beliefs should supplant the findings of mainstream science”(p. 95).

highly readable historical overview of the evolution-creationism controversy. . . . Evolution is not just another scientific topic for many students. The fact that learning about evolutionary theory has cultural and religious implications for defining one’s identity makes the publication of this book important for secular and non-secular people alike. The authors make a strong contribution to public understanding of this controversy by approaching the issue from both historical and epistemological perspectives.

it is unproductive to view the dispute between evolution supporters and evolution opponents as a dispute about science. Rather, the dispute between evolution supporters and evolution opponents should be seen as one part of the US legacy of religious dissent and cultural pluralism in public schools. If creationists and proponents of intelligent design are viewed as cultural dissenters with the same kinds of rights and responsibilities as other minority groups, then it is possible to think about how to create public school communities that are broad enough to include these dissenters on equal terms. While teachers have an obligation to teach evolutionary science to students, they also have an obligation to honour student autonomy, and to acknowledge the legitimacy of the deep interests of students in cultural identity, continuity, and community. . . . Even those who are not fully persuaded by the policy prescriptions that Laats and Siegel provide will profit from reading this historically and philosophical informed book. The topic is very important; the treatment is careful, accurate, innovative, and fair. Two thumbs up from me.

After reading Teaching Evolution in a Creation Nation, I considered ginning up a

seminar in the history of science just to have the pleasure of discussing this lively,

accessible book with students. . . . The argument is optimistic, but not impractical. Like the book itself, the suggestion combines thoughtful logic with a generous respect for the varied participants in this ongoing conflict. . . . The book does an excellent job connecting seemingly isolated dots, explaining how cultural and intellectual realignments during periods of seeming silence on evolutionary education later helped to ignite serious conflict. New approaches to science and university education in the early twentieth century, post-war consensus among biologists about the legitimacy of the evolutionary synthesis, evangelicals’ increasing disillusionment with mainstream schooling and science in this same period, and the emergence of the concept of “intelligent design” all shaped the evolution battles that punctuated the twentieth century. . . . The book is a case study in how to write smart and short. It also offers some excellent examples of basic historical and philosophical procedure — chapter three is a model of how to approach seeming silence in the historical record. It is the perfect length for an introduction to the topic, and a welcome addition to the field’s literature.

Fundamentalism and Education in the Scopes Era: God, Darwin, and the Roots of America’s Culture Wars

Palgrave Macmillan, 2010

Among historians, the Scopes Trial of 1925 hogs all the attention. In my first book, I wondered what else conservative evangelical Protestants wanted out of American education. The answers I found surprised me.