[Update: Here we go…starting the outlining, and very grateful to the many sources of funding and research material. Special thanks to the National Endowment for the Humanities, which sponsored a year of full-time work on the book. Thanks also to the American Antiquarian Society, Massachusetts Historical Society, and New York State Archives, and also to the Charleston County (SC) Public Library, Georgia Historical Society, Newberry Library, Clements Library at the University of Michigan, North Carolina State Archives, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, Louisiana State University Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections, Syracuse University Special Collections, and Swarthmore College Special Collections.]

Why is school reform so difficult?

There are good answers out there: I still remember the first time I read David Tyack’s and Larry Cuban’s answer. It blew my mind. Once they explained it, the truth seemed so obvious. It lined up so well with what I had seen as a high-school teacher. Over and over, reformers with too much power and too little experience in real schools had ignored the simple, essential fact: Teachers embrace reforms that help them do the difficult things they are already trying to do. They ignore the ones that don’t.

In my new book, I’m trying to spell out the other obvious answer from history, an answer so obvious I don’t know why it isn’t talked about more often. The most important people in schools—and the ones with the most impact on how schools look and function—have been strangely ignored by historians and policy-makers alike, even though their choices have been inarguably the most influential in shaping public schools.

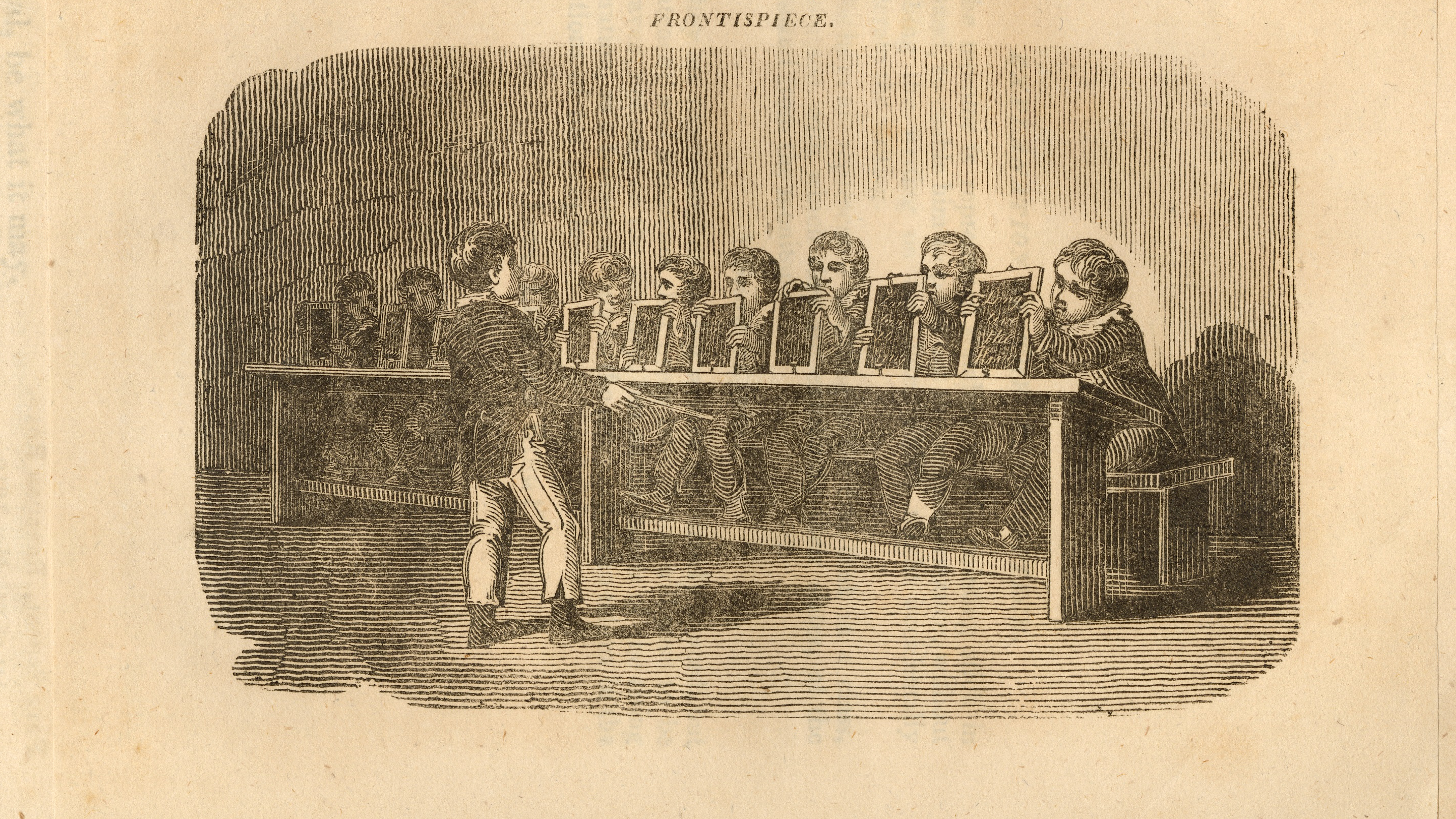

I’m talking, of course, about the school children themselves. In my new book, I’m arguing that children decisively shaped US public schools as schools evolved from 1790 to 1860. It was children who determined the failure or success of every structure, every plan, and every reform idea. Certainly, adults were important. But when we wonder why public schools don’t look the way Joseph Lancaster or Horace Mann envisioned them, we need to examine the most important answer—the influence of children.

Children didn’t just tweak schools here and there. No, in every fundamental aspect—who was considered a possible teacher, what textbooks could be used, how often schools would meet, whether teachers could beat children, whether Black and white children would attend together, what religion would be preached—in every aspect, the role of children was the most important factor.

Putting children at the center of the story does more than just offer a better explanation for the tortuous history of school-reform efforts. It also allows the story to expand beyond the limits of adult-centered histories. Without considering the children—all the children—histories end up focusing on white, middle-class-dominated institutions. This has been true for even the best, most nuanced histories, like the late Carl Kaestle’s Pillars of the Republic (1983). Great historians have tried to expand the story, but focusing on adults means replicating adult divisions. It means telling the history of US public schools as a white-dominated enterprise with some important exceptions.

On the other hand, for the past fifty years historians have been digging into the lives of children in the past. Scholars like Kabria Baumgartner, Karen Sànchez-Eppler, Holly Brewer, Patricia Crain, Courtney Weikle-Mills, and many more have studied what children were doing, what they were thinking, and what adults were thinking about them.

But no one has connected that scholarship to the early evolution of public schools. I will put children at the center of that story, where they belong. When you do that, you can’t help but acknowledge the painfully obvious fact of antebellum American life. Namely, most children spent most of their time doing things other than attending school. Schools did not shape children–children shaped schools. Children’s lives were the things that nurtured and guided schools as one possibility, or, for many children, one impossibility.